Criminalizing Poverty

No Easy Pass for Transit Riders

Jeff JonesHarold Stolper

Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance’s recent move to decriminalize fare evasion has led to a flurry of impassioned responses over how New York City should be addressing the low-level infraction of turnstile jumping. The fact that the NYPD so frequently arrests people for being too poor to access public transit is a stark reminder: until we improve transit access for the neediest New Yorkers, fare evasion will remain a commonplace act of desperation.

But focusing solely on arrests for fare evasion also obscures other troubling disparities in how the city treats transit riders versus drivers, namely: drivers who fail to pay for services such as parking and tolls face substantially lower fines than fare evaders, and are not at risk of arrest or criminal conviction.

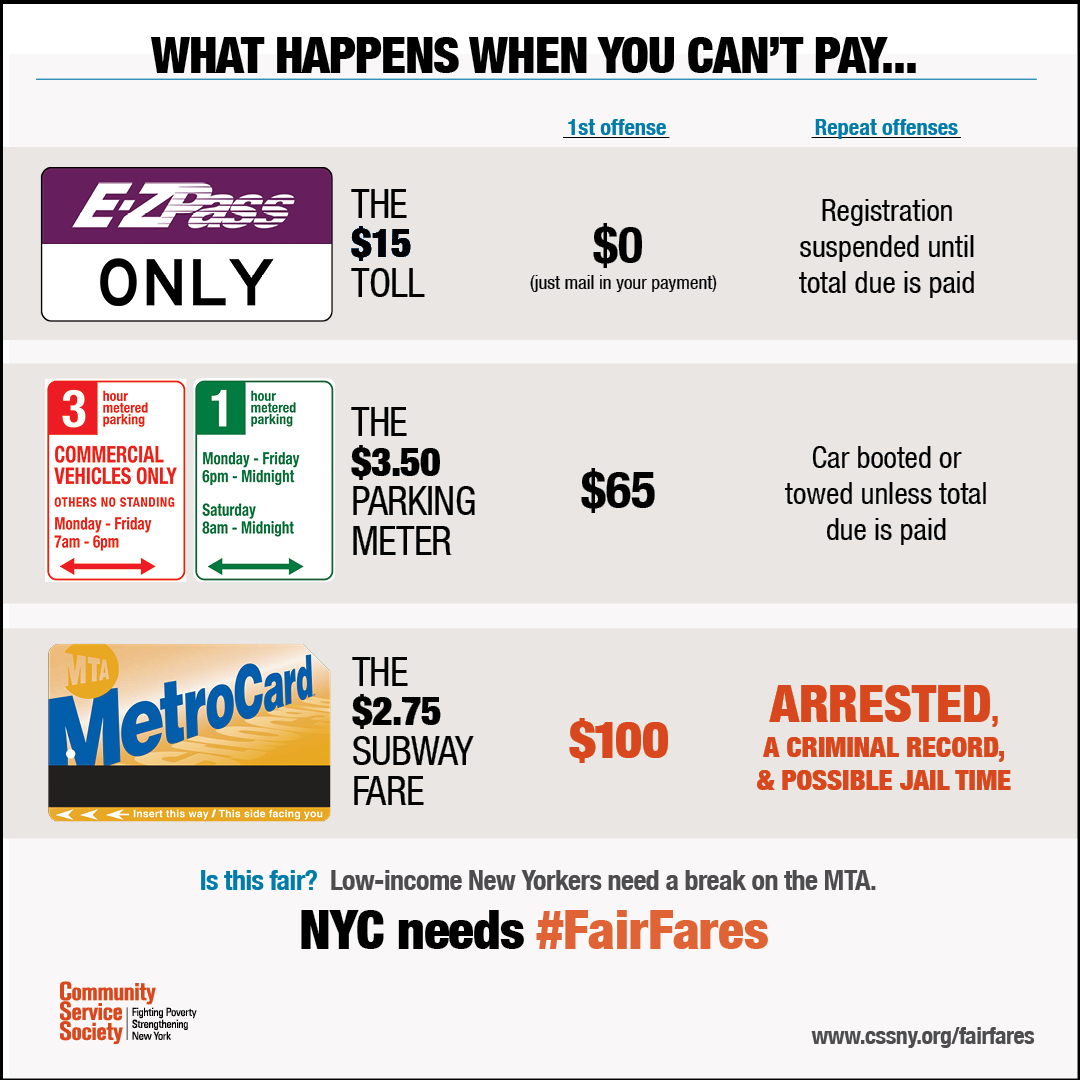

In April of 2016, in response to our research showing the high cost of transit was seriously impeding the economic mobility of low-income New Yorkers, CSS and the Riders Alliance launched a campaign to offer half-price MetroCards to transit riders below the poverty line Throughout this campaign, we’ve heard numerous stories of people crawling under the turnstile because they had no other way of getting home, or sneaking through the gate when they realized both their MetroCard and bank account were empty. When these riders do get stopped by police, if it’s their first offense and they have an ID on them, they are unlikely to be arrested. However, they are handed a $100 fine in the form of a Transit Adjudication Bureau (TAB) summons (source).

$100 for not having $2.75. That’s over 36 times the amount they failed to pay at the turnstile.

How does this penalty compare to fines imposed on drivers for “evading” the tolls and fees from driving and parking?

Let’s start with parking meters. When someone fails to pay $3.50 for one hour of parking in downtown Manhattan, they could receive a $65 ticket—around 18 times the original parking fee. If they parked above 96th street or in any of the outer boroughs, they would be subject to a fine of $35 (see list of parking fines here).

What about evading tolls?

If you travel into NYC via a Port Authority bridge or tunnel, the required toll is $15. If you don’t have enough money at the time, no problem. You have the option to mail in the toll amount, without any additional financial penalty, anytime in the next fifteen days (source). On MTA-operated bridges and tunnels (e.g. the Verrazano Bridge and Battery Tunnel), tolls range anywhere from $4.25 to $17. These crossings no longer have toll booths, so if you don’t have an E-ZPass you simply get an invoice in the mail and have the opportunity to pay your toll, penalty-free, within 30 days (source).

How generous of our regional transportation authorities, to give drivers the benefit of the doubt and considerable flexibility to pay for transportation services they used without paying! Transit users who are caught not paying, on the other hand, are immediately issued a fine (and in some cases handcuffed and arrested).

What if you fail to pay the toll within the time allotted? Depending on who operates the toll bridge or tunnel you’re using, you’ll receive a fine of $50 (from the Port Authority) or $100 (from the MTA). Failure to pay eventually results in the suspension of your vehicle registration until you pay off your debt (source).

Failure to pay your parking tickets? Once you rack up $350 in unpaid fines, your car may be booted or towed and will be held until you can pay off your debt (source).

If you’re a transit user and you are caught jumping the turnstile more than three times in two years, in addition to the $300 dollars in summons fines you could owe, you meet the NYPD’s criteria for arrest. This means that a three-time turnstile jumper must pay $300 for only $8.25 in unpaid MetroCard swipes, and faces the possibility of days in jail and a criminal record. By comparison, a three-time toll-evader who has to pay between $150 and $300 in fines for up to $58 in unpaid tolls, faces no risk of arrest, and can eventually have the boot removed and their registration reinstated without the permanent mark of a criminal record. As if it never even happened. MTA turnstile jumpers, on the other hand, don’t even have a chance to pay their way back into good standing.

The disparity in treatment here is pretty clear. Drivers who repeatedly don’t pay are assumed to be good, law-abiding citizens, and as such are granted considerable flexibility to pay their fees and possible fines. They also face no risk of arrest or a lasting criminal record. Transit users who repeatedly don’t pay are often arrested, risking a criminal record that could hamper their employment prospects for years to come. City policy is thus branding thousands of non-paying transit users as criminals, but is not treating non-paying drivers with the same heavy hand.

Why are drivers who don’t pay treated so differently from transit users who don’t pay? It’s certainly plausible that higher transit fines and more severe penalties are an effective deterrent to wider scale fare evasion. We know of no evidence that suggests the penalties should be this much higher than driving-related penalties, and no evidence that suggests criminal consequences are an effective deterrent.

What we do know is that criminal consequences handed out by the NYPD effectively criminalize poverty. We also know that most people arrested for fare evasion are people of color—blacks make up two-thirds of those arrested for fare evasion in Brooklyn in 2016, and less than one-third of all poor adults in Brooklyn.

So taken together, the city is making it policy to fine poor New Yorkers who can’t afford a MetroCard—predominantly people of color—into even deeper poverty, and funneling many of them into the criminal justice system (the NYPD made more than 4,600 fare evasion arrests during the first three months of 2017).

This is a clear recipe for reinforcing existing disparities in economic means and criminalizing poor people of color. This is about as far as any city could get from progressive transit policy. And it’s happening in New York City, with a mayor who somehow still clings to the claim that he is doing everything he can to narrow the economic divide through progressive policies.

Meanwhile, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance has taken steps to prevent most fare evasion arrests from being criminally prosecuted in Manhattan, instead using diversionary programs and summonses so that the very worst outcomes can be avoided. But if we are to rely on fines as a punishment and deterrent for fare evasion, then it should be applied fairly—fairly with respect to how the city and other public authorities treat drivers who fail to pay for parking and tolls.

Fare evasion deterrence is a valid and important policy issue in the best of times, even more so for a transit system in crisis. But the real solution to fare evasion driven by economic need doesn’t lie in a $100 fine or an arrest, but in making transit affordable to all New Yorkers. How the city treats poor New Yorkers who feel forced to choose between the fare and basic necessities is central to creating a city where economic and racial justice are more than just political buzzwords.